This is third in a blog post series sharing some of my research for Eye of the Beholder & Other Tales:

Mummies…

Curses…

Madness.

Since the middle ages, Bedlam has been synonymous with disorder and mayhem, striking fear into citizens. Bedlam, and therefore madness, was a thing to fear. To be sent to Bedlam was to be forgotten. You could likely die (5) and be buried there (3).

The original Bethlehem Royal Hospital opened in 1247 and was a house for the poor and centre for collection of alms (3). The first recorded insane patients (named ‘lunatics’) were in 1403 (2). The term Bedlam was first used during the fourteenth century- a corruption of Bethlem, or Bethlehem.

In 1598, visiting Governors observed ‘the hospital was “filthely kept”, and a later inspection found inmates actually starving.’ (2). By 1600, Bedlam was co-owned by the Crown and the City of London Crown. During the sixteenth and seventh centuries conditions remained filthy and appalling, not helped by the fact it was built over a sewer, which often leaked into the buildings (2).

The word Bedlam was already in common use by the mid-1600s, used to describe ‘state of madness and choas’. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines bedlam as ‘a place, scene, or state of uproar and confusion.

In 1675, the hospital was moved to Moorfields and then to St George’s-fields in 1814. A new wing was added from 1838 (9).

During this time, money was raised by charging unrestricted access of public visitors to view the inmates – at the cost of a penny. (2). Violent inmates were put on display (4, p2). Viewing became a popular pastime, with ‘swarms of people’ parading through Bedlam in 18th century. After 1770, visitors were required to have a ticket signed by a governor of the hospital (2).

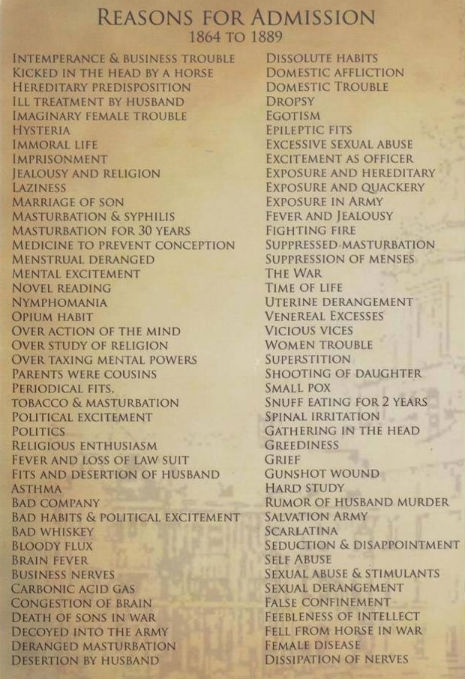

Reasons for admission to a nineteenth century asylum were varied. The following meme (based on an admissions document from the West Virginia Hospital for the Insane,1864-1889 (10, 11, 12).) says it all. Of course, it didn’t help that those with epilepsy, learning difficulties and dementia were classed in the same group as people suffering from paranoia, schizophrenia and depression. (2, 14).

The 1823 book, Sketches in Bedlam, not only listed the process for admission to the asylum, but exclusions for admission, length of stay and details of conditions – provided their complete recovery could ‘be effected within twelve months from the time of their admission upon payment, if the patient is sent by relatives or friends and if such patient is a parish pauper or has received alms or support from any public body or community’ (14). Payments of which were not ‘returnable unless the patient dies or is discharged within one month after admission nor in any case where deception has been practiced upon the hospital by a false statement’. (14).

From November 22, 1841, patients were admitted by petition to the Governors from a near relation or friend (14). If a relative could secure the signature of a physical surgeon or an apothecary, asylum admission could be secured.

Those excluded from admission to Bedlam included:

- lunatics who are possessed of property sufficient for their decent support in a private asylum and also those whose near relations are capable of affording such support

- Those who have been insane for more than twelve months

- Those who have been discharged uncured from any other hospital for the reception of lunatics

- Female lunatics who are with child or who have before been discharged from this hospital in consequence of their pregnancy having been discovered

- Lunatics in a state of idiotcy afflicted with palsy or with epileptic or convulsive fits

- Lunatics having the venereal disease or the itch

- Those who are so weakened by age or by disease as to require the attendance of a nurse or to threaten the speedy dissolution of life or who are so lame as to require the assistance of a crutch

(list from Sketches in Bedlam)

Various cures included:

- purging and bloodletting, (9, 4)

- shock treatment including dousing in hot or ice-cold water (4)

- blistering, threats, physical restraints, such as chains, manacles (6) and straightjackets. (4)

- drugs could be administered to hysterical patients to exhaust them (4)

- Moral treatment (late 1700s)

- electrical shocks (later 19th century)

Moral treatment was a form of moral instruction, introduced by William Tuke. It was believed that immorality and vice caused madness (2) (It should be noted syphilis was common and led to insanity), therefore the chances of recovery were increased if the patient was treated like a child rather than an animal (6). Patients were expected to clean, garden, take tea, dine, make polite conversation and consider the consequences of their actions.

In 1815-16, a parliamentary inquiry, with testimonies by Edward Wakefield, eventually lead to reforms. By (mid – late) 19th century, Bedlam was changing.

The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 concerned the able-bodied poor but did not clearly establish the non-able bodied or offer any alternative to caring for the sick in their own homes. (4). In 1866, The Association for Improvement of the Infirmaries of London Workhouses was set up. Florence Nigthingale proposed a bill for including ‘that the sick, insane, incurable and children should be dealt with in appropriate and separate institutions.’ From 1867, the Metropolitan Asylums Board played an increasing role in caring for the health of London’s poor (6).

The emphasis of care of patients shifted from control, with physical restraints, to moral management using a punishment/reward system. Bedlam became more humane under William Hood, Chief Medical Superintendent in 1853 (6).

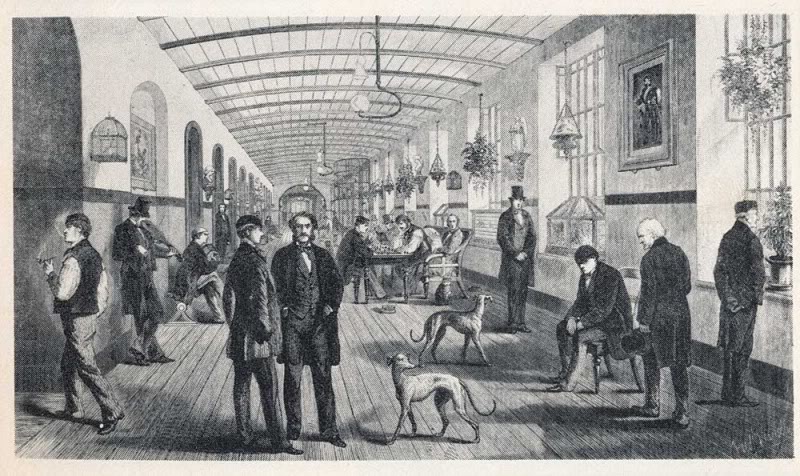

Pictures in the Illustrated London News (1860) showed Bedlam changed from the dark, dreaded place of the 1500s to that of an open, airy residence with communal areas, birds, potted plants and light (15).

[“Womens Ward in 1860” (Illustrated London News, 24th March 1860)]

[“Mens Ward in 1860” (Illustrated London News 24th March 1860)]

Society’s changing attitude toward Bedlam was summed up by Sir James Coxe who addressed the 1877 Select Committee on the Operations of the Lunacy Laws:

“I think it is a very hard case for a man to be locked up in an asylum and kept there; you may call it anything you like, but it is a prison.” (6).

By 1890, the sexes were no longer segregated (8) and, finally, the status of ‘lunatics’ was changed, by parliamentary legislation, from prisoners to patients. (6).

Websites:

- A Drunkard is Madde for the Present, but a Madde Man is Dunke Alwayes https://animalmadness.com/2011/05/30/a-drunkard-is-madde-for-the-present-but-a-madde-man-is-drunke-alwayes/

- A History of Bedlam, The World’s Most Notorious Asylum: Dance’s Historical Miscellany: http://www.danceshistoricalmiscellany.com/history-bedlam-worlds-notorious-asylum/

- Bodies found in Old Bedlam Hospital

http://www.reuters.com/article/us-britain-bedlam-idUSTRE73726420110408 - The History of Mental Illness: from Skull Drills to Happy Pills. http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/283/the-history-of-mental-illness-from-skull-drills-to-happy-pills

- 13. Mental Institutions: Science Museum Brought to Life.

http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/broughttolife/themes/menalhealthandillness/mentalinstitutions - The Metropolital Asylums Board http://www.workhouses.org.uk/MAB/

- Moral Treatment. Science Museum Brought to Life. http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/broughttolife/techniques/moraltreatment

- Under the Dome: Bethlam Blog https://bethlemheritage.wordpress.com/2011/10/11/under-the-dome-notes-on-the-chapel/

- Victorian London – Health and Hygiene – Hospitals – Bethlehem Hospital

http://www.victorianlondon.org/health/bethlehemhospital.htm - 50 Ways to Commit Your Lover http://www.snopes.com/reasons-admission-insane-asylum-1800s/

- 125 reasons you’ll get sent to the lunatic asylum http://www.appalachianhistory.net/2008/12/125-reasons-youll-get-sent-to-lunatic.html

- List of Reasons for Admission to an Insane Asylum. http://dangerousminds.net/comments/list_of_reasons_for_admission_to_an_insane_asylum

Journals:

13. Mania, dementia and melancholia in the 1870s: admissions to a Cornwall asylum. J R Soc Med. 2003 Jul; 96(7): 361–363. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC539549

Books:

14. Constant Observer. Sketches in Bedlam; or Characteristic traits of insanity, as displayed in the cases of one hundred and forty patients of both sexes, now, or recently, confined in New Bethlem. London, Sherwood, Jones. 1823 https://archive.org/details/39002086347292.med.yale.edu

Photos: