Modern forensics is amazing. Scientists can tell you blood type, DNA profiling, retrieve fingerprints from most unlikely places. If there is evidence, the culprit can be identified. We take it for granted. But did you know DNA wasn’t used until 1985?

In 1888 – at the time of Jack the Ripper – policing was a lot different than it is today. Scotland Yard’s Criminal Investigation Department of detectives had only existed since 1878. The media, and the public, thought them a joke. Punch described them the Defective Department and the Criminal Instigation Department (3).

When London was gripped in fear over the Whitechapel Murders, there were few modern procedures to aid in investigation. By the end of Jack’s spree, police investigation was already starting to change – by necessity. One of the most obvious aids to securing the identification of the killer were ‘chance impressions’ – what we call fingerprints.

Let’s take a closer look at fingerprints. Would Doctor Jack linger at a crime scene to wipe it clean?

Not likely. He probably didn’t even know what they were. But the Metropolitan Police did and – if they had heeded the advice of a village surgeon ahead of his time, and that of a Scottish surgeon forty years later – perhaps Doctor Jack may have been identified.

The first recorded evidence of fingerprints was in 1665, when Italian physician, Mercello Malpighi, wrote of the existence of fingerprints (2). The first scientific paper to describe fingerprints was written by English physician, Nehemiah Grew, in 1684 (6):

‘with a Ball he may perceive besides those great Line s to which some men have given Names and those of a middle size call d the Grain of the skin innumerable little Ridges of equal bigness and distance and e very where running parallel one with another And especially upon the ends and first Joynts of the Fingers’.

German, Christoph Andreas Mayer, reported them to be individually unique in 1788 and a Czech physiologist published a thesis discussing 9 fingerprint patterns in 1823.

Scotland Yard’s first chance to use this new technology was in 1840. A village doctor, Doctor Robert Blake Overton, wrote to Scotland Yard, suggesting they check the reported bloody fingerprints found on a bed sheet, in the murder of Lord William Russell. To give them their due, this was followed up, with ‘no such marks’ found. Unfortunately they did not realise their potential and there was no change in investigative procedures (5).

In the meantime, research continued elsewhere in the world, with William Hershel using fingerprints to identify villagers in India in 1858, and Paul-Jean Coulier discovering iodine could reveal fingerprints on paper (1863).

The UK Prevention of Crimes Act of 1871 provided the British criminal justice system with a reason to consider fingerprints. It was now required for convicted criminals to be photographed for future identification. On leaving gaol, criminals had their appearance, distinguishing marks and inked fingerprints recorded, to allow for identification if they should re-offend (8). In 1877, Hershel was fingerprinting sentenced prisoners, in India, to prevent them using fraud to avoid their sentence. Both were using fingerprints to identify existing felons only.

It wasn’t until 1880, that Henry Faulds succeeded in identifying prints on a vial and published a paper in scientific journal, Nature. This led to Scotland Yard’s second opportunity to use fingerprints for investigating a crime.

In 1886, just two years before Jack the Ripper’s reign, Henry Faulds wrote to the Metropolitan Police of London, suggesting the use of fingerprints, citing finger impressions left behind on fragments of ancient pottery. Again the opportunity was dismissed. Perhaps if they had realised their potential to link an offender to a particular crime, we would know Jack the Ripper’s real name today?

Fortunately, the information was passed onto Francis Galton, who continued to study fingerprints and eventually published his book, Finger Prints, in 1892 (7). In the same year, Argentine chief police officer, Juan Vucetich, created the world’s first Fingerprint Bureau. The South Australian Police Force were using fingerprints in 1894 (1) and a fingerprint bureau was set up in Calcutta, India, in 1897.

It wasn’t until 1901 that Metropolitan Police headquarters, Scotland Yard, had its own fingerprint bureau. Britain’s first conviction using fingerprint evidence (for a theft), was in 1902.

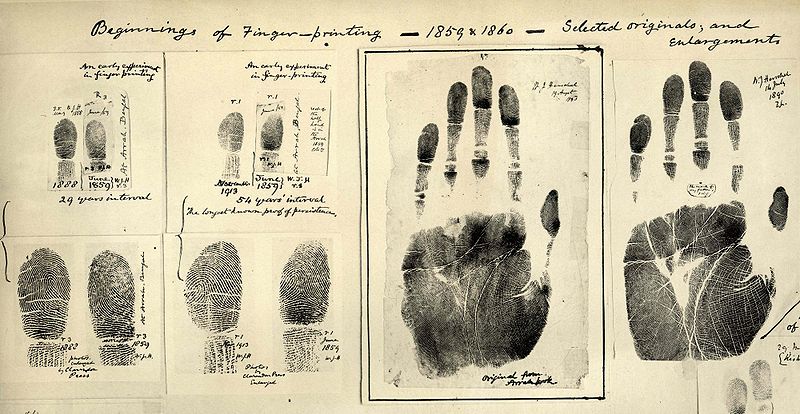

First Fingerprints taken 1859/60 by William James Herschel (2).

Today, fingerprints are not only a means of identifying an individual but they can be collected at crime scenes as a tool for investigation, linking an offender to their crime and aiding to secure a conviction.

References

Webpages

- Australian Police: Fingerprint History http://www.australianpolice.com.au/dactyloscopy/fingerprint-history-1/

- Fingerprint https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fingerprint#History

- Jack the Ripper 1888 http://www.jack-the-ripper.org/investigation-techniques.htm

- South Australia Police Historical Scoiety: http://www.sapolicehistory.org/detectives.html#fingerprints

- Vital Clue Ignored for 50 Years Alberge, Dalya (9 December 2012). “Vital clue ignored for 50 years”. London: Independent. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

Books - Grew, Nehemiah (1684). “The description and use of the pores in the skin of the hands and feet”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 14: 566–567.

- Galton, Francis. Finger Prints. Macmillian, 1892.

-

Worsley, Lucy. A Very British Murder: The Story of a National Obsession, BBC Books, St Ives. 2014