A quick history of photography.

The first successful photograph was taken by Nicéphore Niépce in the mid 1820s. It required several days of exposure (no one could hold their breath that long!) and the result was grainy and crude. Niépce’s colleague, Louis Daguerre, took the first photograph of a human being, having his boots shined on a Parisian street (1838). The Daguerreotype photographic process was commercially introduced in 1839, heralding the birth of practical photography.

The early Daguerreotype required the sitter to remain still for anything up to 3.5 minutes, depending on available lighting (sometimes requiring special implements to hold the sitters head in place, as poor Doctor Henry Collins discovered in The Magic Lantern.) The exposed photograph was then developed, in a special box, for several minutes of exposure to mercury fumes. (Not a quick, or very portable, process.)

Things were about to change.

The tintype (sometimes called ferrotype) process was described by Frenchman, Adolphe-Alexandre Martin, in 1853 and patented in 1856 by by Hamilton Smith (in the United States) and by William Kloen (in the United Kingdom).

Tintypes were created by using either the wet or dry techniques – on a metal plate (which was not made of tin but of polished and lacquered iron instead of the glass plate used for a Daguerreotype). Wet method involved exposing the photographic plate while its collodian emulsion coating was still wet. The dry technique exposed the photographic plate after the gelatin coating had dried. Both produced an underexposed image in the emulsion, allowing for shorter exposure times. The tintype could be developed and fixed in only a few minutes.

Reduced exposure times, quicker developing times and (more importantly) cheaper production costs, , gave rise to the street and carnival photographer. Photography was now available to the general public – no longer restricted to the studio and the rich. Welcome to the world of nineteenth century ‘instant’ photography – the tintype.

The Real Thing.

I ‘d done the research. I knew the theory. I wrote about it in my short story, The Magic Lantern. More recently I got to see the process first hand – in real time – thanks to artist Andrew Dearman. And, for this historical photography enthusiast, it was amazing to watch. Let me walk you through the process.

‘d done the research. I knew the theory. I wrote about it in my short story, The Magic Lantern. More recently I got to see the process first hand – in real time – thanks to artist Andrew Dearman. And, for this historical photography enthusiast, it was amazing to watch. Let me walk you through the process.

The plates are prepared, and placed into the camera, while ensuring the metal photographic plate is not exposed to light when coating with the wet emulsion or placing in the camera (wet or dry versions). A red-light box helps with that. Andrew’s set up allowed me to watch the process. Fascinating.

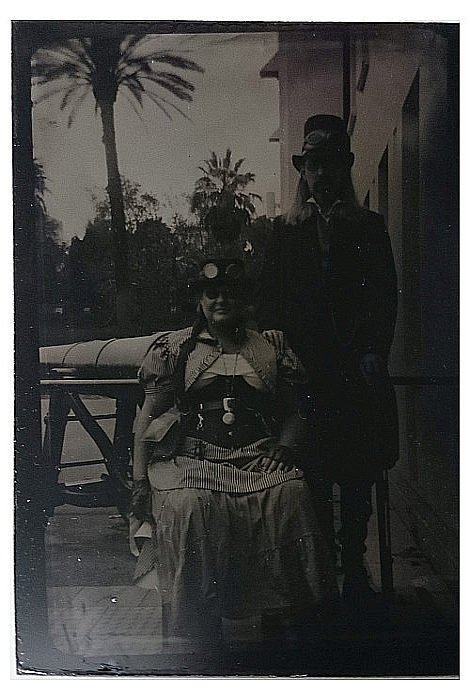

We sat for our portraits. Exposure time (outside, in direct sunlight) was approximately 14 seconds (and I still blinked!). The plate was removed (again in the nifty red light box). The plate was developed for a couple of minutes and rinsed. That is where I panicked. The plate was still black. Not to worry. This is normal. The plate was then placed in the fixing bath. This is where the magic happens. The image appeared before my very eyes.

All that was left was a final wash and time to dry. The entire process took about fifteen minutes and I have my very own tintype photograph with my Dearheart and a unique experience to add to to the list of writing (and photography) research. Tintype (c) 2016 Andrew Dearman.

Tintype (c) 2016 Andrew Dearman.

Other photos (c) 2016 Karen J Carlisle.

All rights reserved.

1 thought on “The Original ‘Instant’ Photograph”